I. Brain assembles scattered facts and forms pattern; clarity ensues.

Here is a swimming hole in a southwest Chinese village in the summer of 1945. I am not 100% sure of all that the villagers did with this water, but they must have done some things of significance or Dad would not have snapped the photo.

This village was a recruiting station for KMT soldiers attached to US OSS for jump, combat, and demolition training for purposes of harassing Tojo’s occupying forces. They learned quickly. These volunteers made excellent soldiers who fought eagerly for their country. In two months they and their mentors conducted multiple missions and did their job.

Later in the summer the team was flown to Kaifeng, from whence they jumped to Hsien for the Hwang-Ho Bridges mission. Here is a scene in Kaifeng, city of canals.

A shadow of a certain kind passed over Dad’s face as he told 12-year-old me, once, I had amoebic dysentery. It was very painful and it took a long time to go away. It was a shadow of remembered pain. He had been lucky: he survived, had never been captured, was not maimed, and his illness did go away. So the illness must have been impressively painful to have caused such a recollection decades on.

Dysentery comes from the Greek for bad gut, bowels gone wrong. Medically, it indicates pain and blood. All diarrhea involves loss of body salts and water. Dysentery severe and prolonged additionally can result in blood-loss anemia. Amoebic dysentery, prolonged and undertreated, can result in liver infection and abscess formation with the protozoan, with consequent liver impairment and jaundice. The creatures can settle in the brain, too; after all, once they get into the bloodstream they have to fetch up somewhere.

|

| The Bug in Evidence |

Our pathogen, Entamoeba histolytica, has an absurdly complex life cycle. In brief, victim-host ingests an encysted form. Organisms excyst in the intestinal lumen, develop into their trophozoite form, and either are excreted or invade the tissue lining the intestine.

Here is normal intestinal lining:

The section has been stained with H&E, hematoxalin (blue, for nuclear material) and eosin (pink, for cytoplasm.) This is from a histopathology text (Figure 24.3) but anyone who has ever nurtured and grown any plant or animal can see that the structures are healthy. Those villi are long and elegant. The cells lining each villus are plump and entire. They can do their work of absorbing sugars, salts, amino acids, water, and so on, and of keeping out toxins and pathogens.

But if the toxins or pathogens are too strong, or the host is weakened, they can damage these defensive structures and effect a breach. Then the germ can go systemic. Here is a CDC photomicrograph of a typical flask-shaped ulcer of intestinal amebiasis. Yep, it is an ulcer all right – a hole in the lining – and the bad guys have poured in. But also note the remaining villi. They are blunted and thickened. Most of their own lining cells are shriveling up or exploding, and so not working well at all. The victim-host cannot absorb much water, nutrients, or medicines. After consuming his store of body fat, he starts to break down his muscle tissue for protein and energy. He becomes weak and cachexic. Yet he continues to fight.

What treatment can be offered a person with amoebic dysentery?

Stop the ingestion of new cysts. Clean up the drinking water, improve general sanitation and kitchen hygiene, and get the human carriers out of the kitchen. Such things were pretty well impossible in rural China in 1945. Oral electrolyte solutions were not generally available at that time, either. Intravenous electrolyte replenishment and intravenous alimentation were only fantasies, on remote battlegrounds.

As far as I can learn, the only antimicrobials available at that time were the sulfa drugs and, more rarely, penicillin. Sulfa would only work if the diagnosis were wrong and the soldier in fact had a bacterial disease. (It presents its own problems as well: it must be mixed with plenty of water to avoid damaging the soldier’s kidneys. And what’s in that water? Something sulfa does not kill?) Penicillin has no effect on enteric protozoans.

We are fortunate now to have metronidazole (Flagyl) which trashes the DNA of microbial cells while doing no harm to host cells. The MDs have that now among their options for killing amoebae that have invaded human tissues. We also have the aminoglycoside drug paromomycin, which gums up the works of microbial ribosomes; the MDs have that among their options for killing amoebae still in the gut lumen. But those were not available commercially until 1960. I can find no evidence that anything like either of them was available, even experimentally, during World War II.

So, a stricken man could only eat and drink the cleanest stuff he could find, and the easiest to absorb, including salt. It was a race to rebuild the intestinal lining, using materials gleaned largely from elsewhere in the body, before those ran out or new waves of the pathogen attacked.

During the war years there were thousands of men in this fix, in all theaters and climates, with the highest rates being in CBI, the China-Burma-India theater. The Army epidemiologists kept records:

In late 1942 and in 1943, increasing numbers of troops entered North Africa and the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and the China-Burma-India theaters, all north of the Equator. Rates for the total Army rose to 25 per 1,000 and for troops overseas to 66 per 1,000, the 1943 annual rate for all overseas troops being the highest of the war. June 1943 marked the high point in monthly rates for troops overseas, the figure being 164 (chart 28). Large numbers of unseasoned young men made a first entry into poorly sanitated areas of highly endemic diarrheal disease. Conditions were different in subsequent years for smaller numbers of men were rotated into already established bases where preventive medicine practices were established and the bulk of troops had become accustomed to conditions. For overseas troops in 1943, 7.4 percent of all disease and 3.5 percent of all noneffectiveness was due to the diarrheas and dysenteries (table 67). Rates for the total Army were better in 1944 and 1945, 22 and 22, respectively. Rates overseas fell from 66 in 1943, to 38 in 1944, and to 33 in 1945 (table 54).

Highest rates were encountered when United States Army troops intermingled in densely populated areas with Eastern peoples, as in China-Burma India, the Middle East, North Africa, and the Philippines. It was at these points of contact with Eastern civilizations that highest rates of diarrheal disease occurred. Diarrheal disease was hyperendemic in these locations into which United States troops were introduced. The criticism was often made that United States troops, accustomed to the advanced sanitary practices of Western civilization, were not sufficiently briefed regarding precautions necessary to prevent personal and mass diarrheal disease in these Eastern locations.

And here is the money quote (emphasis mine):

China, Burma, and India are all hyperendemic areas in respect to diarrheal disease. Many sanitary practices of these overcrowded populations, both personal and communal, are tied to habits and customs of generations past. The saving and collection of night soil for agricultural purposes and the promiscuous deposition of filth including feces and garbage favored survival and spread of the infectious agents of intestinal diseases. Food is commonly unprotected from dust, rodents, and flies. Refrigeration is almost universally lacking. Flies are generally abundant. Diarrhea and dysentery, bacillary and protozoal, are constantly present.

These diseases were quickly established among United States troops entering this environment, where standards of sanitation were so different from those at home. Close contact with the native population was often demanded by the military situation. Native help was almost universally employed in foodhandling throughout the theater.

In the China sector, arrangements existed whereby the Chinese Government provided food and lodging for United States Army personnel. A Chinese Government agency, the War Area Service Command, organized and staffed messes and living accommodations at stations and airfields. Air shipments over “the Hump” were limited to essential military materials, and personnel and sanitation materials had low priority. The United States Army in China, in certain respects, was a nonpaying guest, and severe criticism of sanitation was not considered diplomatic. However, inspections were made by medical officers, and mess sergeants were assigned to supervise. Ultimately, new equipment and sanitation supplies were provided, and a gradual improvement in sanitation was achieved. Separate data for the sectors of the theater are available for the period from November 1944 through December 1945. The China rate for diarrheas and dysenteries was 122 cases per 1,000 troops per annum, contrasted with a rate of 86 for the India-Burma sector. The latter sector had the benefit of a belatedly organized preventive medicine program and the opening of area and research laboratories.

Here’s Dad on the troopship home, passing through Suez headed for Strathclyde. Seasickness may be contributing to the drama in this photo.

They let him go home for a month to recuperate, that Christmas, before having him back in D.C. for prolonged debriefing. He still has smudges under his eyes and an anxious expression.

There is a later photo showing him standing on a scale and smiling a big smile that goes around his face three times. He must have reached some goal for weight gain.

II. Higher-ups enter the story; confusion and obfuscation abound.

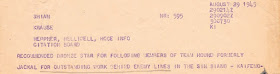

Primary source item dated August 29, 1945 is a mimeographed recommendation for citation. It mentions the entire Team Jackal and summarizes their various actions.

There was a big encampment at Kunming, and they all had to wait around there for some time, so an OSS named Krause had the duty of writing these up.

Importantly, the final two sentences of this recommendation read (emphasis mine): These men all did extremely fine job despite fact they were continually besieged by attacks of dysentary, [sic] diarrhea and worms. Intelligence submitted was also excellent and helped to pinpoint targets for Air Force.

Now contrast this with primary source item dated 13 September 1945. I don’t know the proper term for this 3-page document of which I have flimsy copy; it is a writeup of the reasons for the citation. (The body of the text, edited down by some 15%, appears with similar wording in the citation proper. The rest of this document is attestation of data points concerning the recipient, in the manner of an affadavit, except that it is unsigned.) Nor can I tell which headquarters is meant: HQ in China? in Assam? in D.C.?

The writer added many details about the various missions, for which I commend and thank him.

But he censored out the germs and worms.

Instead there are slick, nonspecific phrases about untiring energy and devotion to duty.

Why do higher-ups do this? Is it personal, or careerist, in that they want to sound suave themselves, rather than crude? This guy could have transmitted the truth that was given to him, using language less graphic. He did not have to write diarrhea. He could have written . . . chronic debilitation due to health conditions in the area of operation. Phrasing of that sort would preserve and transmit the truth while maintaining a tone of propriety. Our soldiers deserve both truth and propriety. They do not deserve to come home to a lifetime of psychological isolation from badly-informed countrymen.

Or is it policy? If so, is the policy of sanitizing reports and citations for some purpose of domestic morale? Or is it to cover mistakes that led to avoidable casualty? Or is it intended to burnish the public image of one outfit that is competing with all the other outfits for, well, everything – replacements, equipment, fame? Did all branches pretty up their reports this way?

What did our WWII Staff and Cabinet think was going to happen when the citizenry found out various suppressed truths as to front-line hardships, as eventually they did, twenty-five years later on the development of wartime news on evening television? What did they think their situation was going to be when the citizenry no longer felt they could believe anything they said?

Was it part of diplomatic policy, as above: severe criticism of sanitation was not considered diplomatic. Was this instance of potential, implied criticism censored to avoid offending the sensibilities of Chiang Kai-shek? If so, that did not work out too well, did it?

This is a case of elision of unpleasant truth just days from the Japanese surrender and, possibly, before leaving China. One step back from the scene of battle, the truth begins to take hits.

This sanitizing of field reports may well have been done for the best of reasons as understood at the time. If on the other hand any single one of the actors on that stage at that time were indeed of the sort against whom Hotspur made his protest, in his own time, then he deserves that same protest, as well. Here Gielgud delivers it, from Henry IV, Part I, I:3.